Each year in November my thoughts turn to Veterans Day. It’s an opportunity to express remembrance and gratitude to those veteran leaders and mentors who thought me worthy by investing some of their precious time, talent, and treasure in my life, personally and professionally. There are too many to name here, so I’ll focus my gratitude and remembrance today with someone who, early on, gave me THE best advice I ever received.

I was 22 years old in 1978 and at a decisive career decision point, trying to land a job as a news photographer. Fortunately for me, Col. Edwin C. “Ned” Humphreys, JR. USAF (retired) was the publisher and editor of a small weekly newspaper in Mobile, Alabama, and he was hiring. I remember reading his ad in the employment section of the newspaper (yes Kids, such a thing existed then) and immediately called to confirm an appointment. In my excitement at getting an interview, I was reminded by my older brother, Rod, that I was uniquely unqualified for the position, having no experience other than the enjoyment of taking pictures on Kodak instant cameras and the occasional 35 mm borrowed from friends or family. Fortunately, Rod WAS an exceptionally good and experienced aviation photographer, and was happy to tutor me through a twenty-four-hour crash course in film development.

This was old school photography, when film was packaged in rolled canisters and developed in a darkroom using various chemicals. I’m sure my sister-in-law Joyce was less than pleased when she discovered the toxic chemical spill we left behind in her kitchen, which we converted into a darkroom the evening before my interview. Rod was a patient and good teacher. Unfortunately, I was a less-than-prepared student.

Armed with limited skills, boundless ego, and a ridiculous overestimation of my abilities, I headed for my interview at the newspaper with Col. Ned. And I flat out rocked our time together. He gave me an assignment on the spot, sliding a Yashica Mat 124G camera (Google it!) across his desk and sending me out to photograph a high school baseball game. The drive to the high school took just a few minutes, which was helpful because I had never even seen a Yashica Mat 124G camera before.

By the time I figured out the box-shaped crank-advance camera is operated by holding it at waist level and looking down into a flat glass viewfinder, the game was already in the sixth inning. I completed the assignment quickly and headed back to the newspaper office, confident of the praise, and an unprecedented pay raise that certainly would be waiting for me to claim.

On arrival, Col. Ned immediately sent me to develop the film and submit my work. That’s where everything happened, and none of it was good. I didn’t know it, but the film wasn’t the only thing about to be exposed.

Inside a pitch-black darkroom, I opened the camera and began to remove the film. My fingers fumbled across something I didn’t expect to find: a two-inch-wide roll of 120-mm film wound around a wooden spool. My overnight crash course in photography had focused entirely on 35-mm format, which is housed in a small metal container less than an inch wide. After several failed attempts to manipulate the cannister and with any reasonable amount of darkroom time long gone, I did the only thing I could think of to solve my predicament and flipped on the small light inside the darkroom—very quickly—just long enough to see how to open the strange roll of film and transfer it to a developing canister.

Darkroom Rule #1: never turn on the light while handling an open canister of film. I exposed the entire roll. I had nothing and I knew it. Col. Ned was waiting for me on the other side of the darkroom door. Time to face the music.

“How did it go?” he asked.

I briefly considered trying to bluff my way through the absolute failure, blaming a faulty roll of film, diluted darkroom chemicals, a malfunctioning camera, or phantom light streaks inside the darkroom. Instead, I just confessed. “I messed up.”

“Yes, you did,” said Col. Ned, who then explained my interview hadn’t quite been the slam dunk I believed it to be. He knew immediately I was completely unprepared for the task at hand. This was, as we say in Texas; not his first rodeo. My responses to his strategically probative questions had exposed all my lies and limitations, especially concerning darkroom technique and film development. Knowing this, Col. Ned, a great leader, sent me out to learn a life lesson I would never forget.

The baseball game I was assigned to shoot was a doubleheader, and he already had assigned a photographer for the first game. He thought I might be able to take the photos, but he really didn’t care one way or the other. He was looking to see how far I would push the lie and how I would respond when exposed as a complete fraud. Busted, embarrassed, and totally humiliated, I knew the interview was done and the prospect of a job with it.

As I rose from the chair, which I had steadily been sinking into for several minutes, Col. Ned said two words that changed my life: “You’re hired.”

I froze, completely dumbfounded, and that’s when Col. Ned Humphreys gave me THE Best Advice I Ever Received; wisdom that any prospective leader and team member should commit to memory. I refer to it as “3 Things I Learned in the Dark” (literally).

With a commanding gaze and stern voice perfected through years of military service, he said; “young man, if you ever want to be successful and not fumble around in the dark, there are three things you must do every day.”

-

- “You can’t fake it until you make it, so Ask for Help.”

-

- “Own your Mistakes.”

-

- “Change the thing that makes you lie.” (that stung and stuck!)

Those “3 Thing” have become my road map for leadership success. From that day forward I tried to be prepared for any task assigned to me. I became dedicated to lifelong learning. I asked questions and asked for help. And I NEVER wanted to disappoint Col. Ned Humphreys.

He was the definition of a full-throttle leader. He was patient, helping every employee push beyond their limitations. Failure was expected, but never accepted. If you owned your mistakes, learned from them, and improved, you were back at it the next day. If not, you didn’t stay around long. Col. Ned always found ways to encourage and mentor every member of his staff. He helped us get where we wanted to go. And he made sure we arrived there, humble, grateful, and always prepared.

I share his story often when discussing leadership, and devoted an entire chapter to Col. Ned in my book, “Full-Throttle Leadership: Passsion, Power & Purpose on the Edge of America.” He embodied, what leadership expert John Maxwell meant when he said; “A leader is one who knows the way, goes the way, and shows the way.”

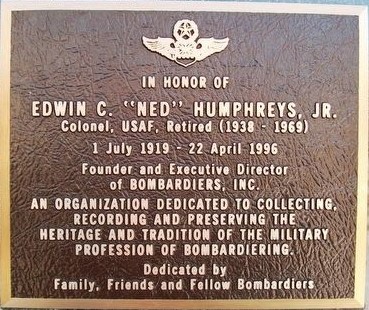

In 1947, Col. Ned Humphreys founded Bombardiers Inc., an organization dedicated to collecting, recording, and preserving the heritage and tradition of preserving the military profession of bombardiering.

That collection now resides in the Office of Air Force History at Maxwell Air Force Base.

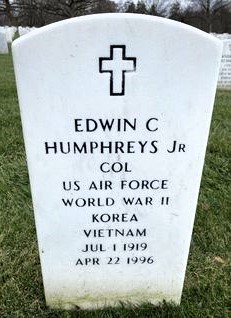

Col. Humphreys died on April 22, 1996, and was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

An honorary plaque in his name is displayed at the National Museum of the US Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton, Ohio.